By Leroy W. Demery, Jr.

A news story, published online at 2018 August by several outlets, states that South Korea had decided to close its “high-speed rail” line between Seoul and Incheon International Airport. This claim was repeated by several highly unreliable anti-rail sources in the United States and elsewhere, though it was incorrect.

The story contains several statements that are incorrect or misleading. Seoul does have an airport railway, but it is not “a high-speed rail line” – and continues in operation. Some “KTX” high-speed trains were extended from Seoul station to Incheon Airport from 2014, but these were withdrawn early in 2018 because of low ridership and capacity issues. This cancellation of service was made permanent from the beginning of 2018 September (reinstatement has been outlined as part of long-term plans).

The errant story originated – apparently – in Korea and was first published by a Japanese media outlet. Online evidence suggests near-simultaneous publication Japanese- and English-language versions – both of which present content that deviates substantially from well-known and widely reported facts. Several types of “problematic content” are present, but evidence of purposeful deception is lacking.

LINKS (arranged in order of online publication):

韓国高速鉄道、4年で廃線 ソウル-仁川空港間 kankoku kōsoku tetsudō, yon-nen de haisen Seoul – Incheon-kūkō kan. (日本経済新聞 nihon keizai shimbun (“Nikkei-J”), August 15, 2018, 20:30.)

South Korea to shut down Incheon Airport high-speed rail. (Yamada, Kenichi. 2018. Nikkei Asian Review (“Nikkei-E”), August 16, 2018, 04:56 JST.)

South Korea closes $266m high-speed rail line as passengers prefer the bus. (Global Construction Review (“GCR”), 16 August 2018.)

Korea abolishes Seoul – Incheon Airport High-Speed Rail Line. (Cox, Wendell. 2018. New Geography (“NG-Cox”) August 17, 2018.) This a particularly untrustworthy website.

Notes: The Japanese-language story was published by 日本経済新聞, Nihon Keizai Shimbun. This is a long-established media outlet known today as the world’s largest financial newspaper. The parent company, 日本経済新聞社, Nihon Keizai Shimbun-sha, uses the English-language title “Nikkei, Inc.” “Nikkei Asian Review” is the English-language version of the online edition of Nihon Keizai Shimbun. The Japanese-language story has the byline ソウル=山田健一, “Seoul: Yamada Kenichi;” both the Japanese- and English-language versions of the Nikkei story were credited to the same person.

The “Nikkei Asian Review” story was referenced by both the “Global Construction Review” and “New Geography” stories.

All stories cited above were retrieved on 2018 August 29. The links were checked on 2021 February 21.

FACTS

1.) There is no “Incheon Airport high-speed rail” line.

2.) Seoul’s “AREX” airport railway is not a “high-speed rail” line.

3.) Service withdrawn (“abolished”); no infrastructure closed (“abandoned”).

4.) Actual event: withdrawal of KTX high-speed trains from AREX.

5.) “Low ridership” played up, operating issues ignored.

6.) 303 billion KRW ($266 million) spent for the high-speed rail line . . . NO.

7.) English-language story titles: One “highly misleading;” two “incorrect.”

8.) Japanese-language story title: “possibly misleading.”

DETAILS

1.) There is no “Incheon Airport high-speed rail” line.

No ambiguity here. The definitions promoted by the International Union of Railways (UIC) specify a maximum permitted speed of at least 200 km/h (124 mph).

2.) Seoul’s “AREX” airport railway is not a “high-speed rail” line.

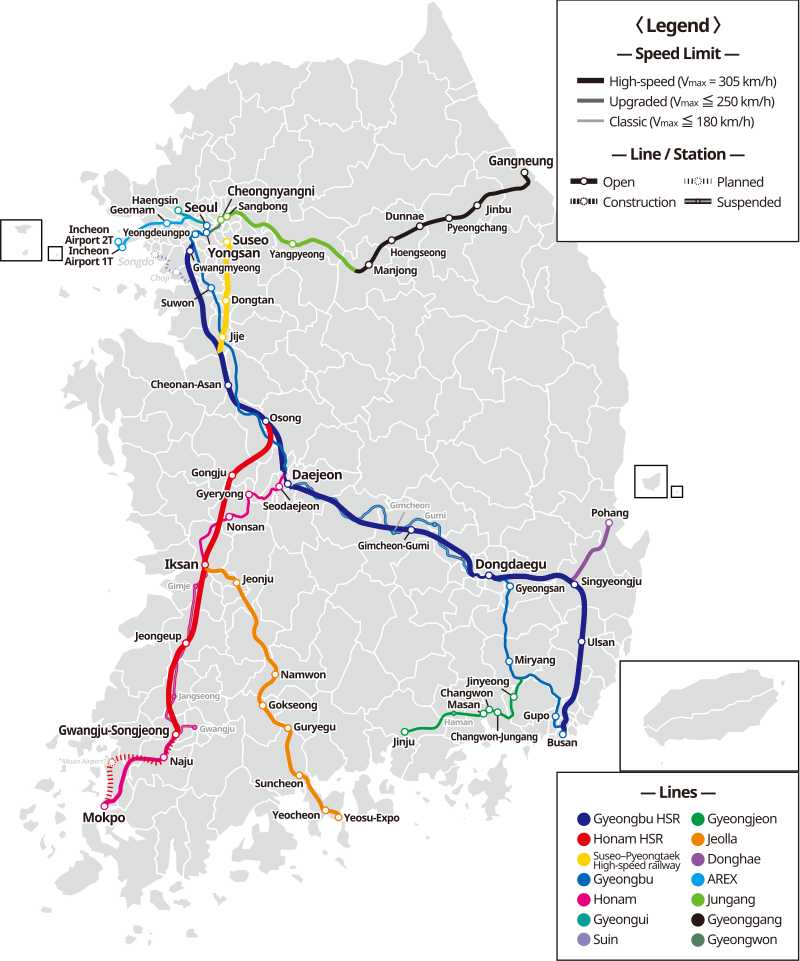

AREX (“Airport Rail Express,” marketed as A’REX) is a conventional electrified suburban railway connecting Seoul station with Gimpo and Incheon international airports (see map). AREX has a maximum permitted speed of 110 km/h (68 mph). No ambiguity here, either.

3.) Service withdrawn (“abolished”), no infrastructure closed (“abandoned”).

The ambiguity issue pertains only to the Japanese-language story. In brief, the same word (廃止, haishi, “abolish” or “abolition”) is used (re. railways) for withdrawal of service as well as closure of infrastructure. To complicate matters, another word (線, sen, “line”) is also used to refer to railway services as well as infrastructure. The meaning is usually clear from context. Again, this applies only to the Japanese-language story. No one reading an English-language article would confuse, say, discontinuance by Amtrak of services branded Acela Regional with closure of the Northeast Corridor rail line.

4.) Actual event: withdrawal of KTX high-speed trains from AREX.

AREX was opened between Gimpo and Incheon airports, 37.6 km (23.4 mi) on 2007 March 23. The second phase extends westward from Seoul station to Gimpo Airport, 20.4 km (12.7 mi), and was opened on 2010 December 29. The line was extended 5.8 km (3.6 mi) eastward to the new Incheon Airport Terminal 2 on 2018 January 13. The completed line extends 63.8 km (39.6 mi).

Selected KTX high-speed services were extended over AREX to Incheon Airport on 2014 June 30, following completion of a track connection at Susaek, northwest of Seoul station. This created operating problems for AREX but the KTX service was continued, in part because of plans for the 2018 Winter Olympics. This event, marketed as PyeongChang 2018, was held between 2018 February 8 and 25. Operation of KTX trains on the AREX line was suspended on 2018 March 23. The national railway operator Korea Railroad Corporation, which trades as Korail, proposed in June that the suspension be made permanent. Reasons stated were low ridership, and operating issues which caused delays to passengers. The Ministry of Land and Transport gave its approval on June 30, and permanent cancellation took effect from September 1.

5.) “Low ridership” played up, operating issues ignored.

Korean-language outlets reported during 2018 June and July that the suspension of KTX service to Incheon Airport would be made permanent – and stated low ridership and operating issues as the primary reasons.

Both versions of the Nikkei story – Japanese and English – played up “low ridership” but ignored the operating issues. These problems were certainly known in advance and must have become apparent from the beginning of KTX service to Incheon Airport. Sharing of tracks by high-speed trains and regional services is not necessarily a good idea.

As stated above, the maximum permitted speed on the AREX line is 110 km/h (68 mph). However, KTX trains were permitted a higher maximum speed: 140 km/h (87 mph). In order to maintain safety standards, the average interval between trains had to be increased when a KTX train was present on the line, causing a reduction from 18 to 12 trains per hour per direction – and from 420 to 357 trains per day. This was a substantial capacity constraint on a railway with heavy – and growing – traffic.

Another problem: KTX trains could not be towed by AREX trains in case of breakdown, requiring use of diesel locomotives – and consequent delays to passengers. Two such incidents took place during 2017.

At 2013 September, AREX trains averaged about 152,000 passengers per day. The great majority of this traffic was carried on “General” (= “Normal,” or “Ordinary”) trains, marketed in English as “All stop” trains. AREX also operates “Direct” (“Express”) trains, a premium service that does not serve intermediate stations – and costs nearly twice as much as “All stop” trains. The express trains carried about 2,000 passengers per day, less than two percent of overall daily traffic.

AREX trains averaged about 240,000 passengers per day by 2018. The airport railway company – a Korail subsidiary since 2009 – stated that without KTX, it could increase service to accommodate up to 280,000 passengers per day.

Prior to opening of the 2018 Winter Olympics, KTX trains provided 11 departures per day from Incheon Airport: six Gyeongbu (to Daejeon, Daegu and Busan), two Honam (to Gwangju and Mokpo), and one each of Gyeongjeon (to Masan and Jinju), Donghae (to Pohang) and Jeolla (to Jeonju and Yeosu). An equal number of services to the airport were provided. Unfortunately, the planned 160 km/h (99 mph) maximum speed was not attained – and the planned travel times could not be achieved. Fares charged for KTX services were twice as high as charged for AREX “All stop” trains. KTX airport service was infrequent and expensive, and offered only the convenience of “one-seat” travel. The Ministry of Land and Transport reported at the time of service suspension that traffic averaged just 15 percent of capacity.

6.) 303 billion KRW ($266 million) spent for the high-speed rail line . . . NO.

Both versions of the Nikkei story – Japanese and English – stated that the cost of the “rail project” at 303 billion South Korean won (KRW), or $266 million (USD).

The Nikkei stories reference “South Korean daily Chosun Ilbo” (the GCR and NG-Cox stories reference “Nikkei Asian Review”).

We are not certain where this amount came from, and what it represents. It falls far short of the cost of building a dedicated high-speed rail line more than 60 km (40 mi) across one of the world’s most densely-populated urban areas.

A 2013 news story (Lee) states that, according to the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, the cost of building the AREX railway was 4,218.4 billion KRW (about $3.85 billion). This works out to about 68.4 billion KRW ($62 million) per km (about $100 million per mile).

The same story states that the cost of implementing KTX service to Incheon Airport (which was not planned at the start of AREX construction) was 455.6 billion KRW (about $416 million). This would include cost of building the track connection (2.9 km / 1.8 mi) and whatever infrastructure modifications (e.g. to track, power, signal systems and stations) were needed to permit operation of KTX trains on AREX.

7.) English-language story titles: One “highly misleading;” two “incorrect.”

The English-language story titles are (from above, emphasis added):

Nikkei-E: “South Korea to shut down Incheon Airport high-speed rail.” Highly misleading.

GCR: “South Korea closes . . . high speed rail line . . .” INCORRECT.

NG-Cox: “Korea abolishes Seoul – Incheon Airport High-Speed Rail Line.” INCORRECT.

The “Nikkei-E” article title does not refer unambiguously to closure of infrastructure – although some readers might infer this (online evidence, e.g. travel blogs, make clear that this did in fact take place).

The GCR and NG-Cox stories do refer an event that did not take place: closure (abolition) of infrastructure.

8.) Japanese-language story title: “Possibly misleading.”

The Japanese-language article title (“Nikkei-J”) is possibly misleading but not “incorrect.” The full story title translates literally as:

[South] Korea High-Speed Railway, “abolished line” after four years, between Seoul [and] Incheon Airport.

If it is true that translation is an art as well as a science, then translation of Japanese into English is a fine art. A less-direct but more-readable translation:

[South] Korea High Speed Rail, Seoul – Incheon Airport, Abolished after Four Years.

However, the sentence above might be too long to make an effective news story headline.

The author believe it likely that the intended readership – Japanese-speaking consumers of “business” news – is likely to understand that “abolition” refers to service rather than infrastructure. However, this is certainly not true of all Japanese-speaking Internet users (as evidenced by blog posts).

ASPECTS OF PROBLEMATIC CONTENT

The term “fake news” has become an often-used epithet in the American political lexicon. The story described above has three of the seven types of problematic content (“Mis- and Disinformation”) described by Claire Wardle (Shorenstein Center, Harvard Kennedy Center):

False Connection: Headlines, graphics or captions that do not support content.

Misleading Content: Misleading use of information to frame an issue.

False Content: Sharing of genuine content with false contextual information.

However, two types of problematic content are not present:

Manipulated Content: Genuine content, manipulated for deception.

Fabricated Content: Content, wholly false, presented for deception.

CONCLUSION

With reference to the news stories described above, we find no evidence of purposeful manipulation or deception, and believe therefore that the label “fake news” is not appropriate. However, problematic content does not necessarily arise from purposeful deception. The “Nikkei-J” and “Nikkei-E” stories might be described as virtual textbook examples of inadequate background research and fact-checking; the others suggest bias – pro-highway, anti-rail, anti-high speed rail in particular – to greater (“NG-Cox”) or lesser (“GCR”) degree.

REFERENCES

이동훈. 6조원짜리 돈 먹는 하마… 인천공항 철도의 딜레마. 주간조선. 2013-11-12. (Lee, Dong-hoon. 2013.

“A hippo who ate 6 trillion won . . . The dilemma of the Incheon Airport Railway.” Weekly Chosun. 2013 November 12. Posted on the pub.chosun.com website, which is part of the Chosun Media group. Accessed 2021 February 21.)

Wardle, Claire. 2017. Fake news. It’s complicated. First Draft, February 16, 2017.